Diamonds come in all shapes: heart, pear, marquise, baguette… But the one shape that beats them all is the round brilliant cut: 57 facets polished perfectly, bringing out the diamond’s brilliance, sparkle and fire in the best possible way. Did you know that the brilliant cut has been considered the ideal diamond cut for almost a 100 years now, and there’s a fascinating story behind it?

Let us take you back to Antwerp, 1899. This is the year that Marcel Tolkowsky was born into a leading family in the world of diamonds, consisting of diamond cutters, cleavers and dealers. Following in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, Marcel entered the diamond business, and after studying at the Lycée Français he went to the University of London. Here, he finished his PhD and published the legendary book Diamond Design in 1919, which changed the way we look at diamonds for good.

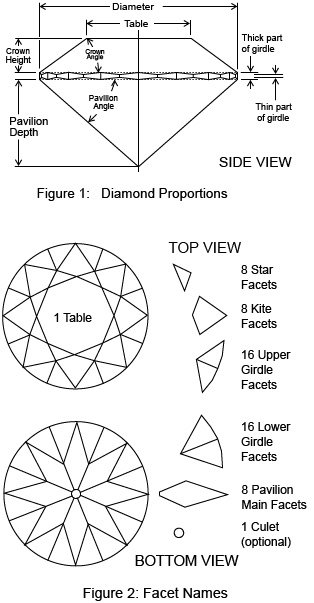

In his book, Tolkowsky is the first person ever to mathematically define the brilliant cut, calculating and describing every small detail that is needed to maximize the brilliance, sparkle and fire of the diamond. By doing this, he established the precise proportions of a brilliant, which remains the benchmark up until today and is often referred to as the ‘ideal cut’.

But first… A little bit of history

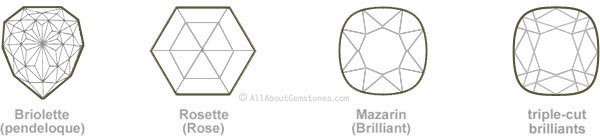

The very first diamonds were found in India in the fourth century B.C. Up until 1728, when diamond deposits where discovered for the first time in Brazil, and more than 150 years later in South Africa, India was the only place in the world where diamonds were found. ‘Polishing’ diamonds has long been limited to smoothing the already existing facets of the crystals as they were found by grinding them against other diamonds, always focused on accomplishing the least amount of weight loss. This started to change from the 15th century, when wearing diamonds as jewelry became fashionable for women. Diamond cutters became more specialized and developed better techniques to polish diamonds with diamond powder. In the decades to come, symmetry became more important and the first standardized shapes were introduced, such as the briolette and the Rose cut.

The Brilliant Cut

The first brilliant cut was introduced in the 17th century known as ‘mazarin’, with 16 facets on the crown or upper side of the stone. A little bit later the Peruzzi cut was introduced by the Venetian polisher Vincent Peruzzi, increasing the amount of facets on the crown to 32. Through a series of gradual transformations and developments over the course of the 17th and 18th century, this evolved into the forerunner of the modern brilliant, the Old European Cut. The old brilliant cuts were always somewhat square-shaped with rounded corners. It was the introduction of mechanical bruting in the 19th century which made it possible to make the stones completely circular, bringing the brilliant round cut as we know it today even closer.

Tolkowsky

This is where Marcel Tolkowsky comes into focus in the early 20th century. Tolkowsky is often referred to as the inventor of the round brilliant cut, but as you can read here this is not entirely true. The round brilliant cut had already been going into style when Tolkowsky wrote his book Diamond Design. What makes Tolkowsky a pioneer in his trade is the fact that he was the first one to make a mathematical analysis of the round brilliant cut, proving it to be the ‘ideal cut’, something which other polishers before him had only based on empirical observations. His findings were revolutionary and set the standard for diamond polishing from that point onwards.

57 Facets

The ‘ideal cut’ contains 57 facets (sometimes 58 if a facet is added to the point at the bottom, the culet). Thirty three on the top part, or the crown, and twenty five on the bottom half, or the pavilion. The thin edge between the crown and the pavilion is called the girdle and can be frosted, smooth or faceted. Today, most girdles are faceted. The proportions are calculated in such a way, that the light refraction within the stone is just right. Would the cut be too shallow or too deep, the light would get lost inside the stone and take away its brilliance and fire.

The analysis of one man changed the way we look at diamonds and how they are polished, and even more impressive: 99 years have passed, and his analysis still holds its ground.